We trust this letter finds you well.

As 2022 approaches the finishing line, we are delighted to conclude another exciting year for our partnership. We closed three new investments in Car & Classic, Planhat and Teamtailor, which is right in line with our aim to make 2-4 new investments per year. The most intense workstream was, however, supporting our portfolio companies in making the most out of the shifting market environment. As discussed at our annual meeting, we appreciate markets characterised by scarcity and the need to both prioritise and optimise over those characterised by abundance, and we look forward to the opportunities the coming year may provide.

“Ouch. It’s been a brutal year”

Jeff Bezos in the Amazon shareholder letter, 2000

Despite the public technology market peaking in November 2021, the private market continued its strong performance through Q1 this year with an increase of 52% in capital raised. The picture changed dramatically in the second half of the year, with the funding raised in Q3 declining by 40% versus the same quarter in 2021. The weak market has continued into Q4 and despite the strong start of the year, total funding is expected to fall by some 15-20% in 2022 versus 2021.

Valuations have seen a similar development. Public markets were the first to fall, with the private market closing the gap by the summer and continuing to decline since. As we write, it is likely that private companies will have fallen further than the public markets by the end of 2022.

Our Q3 2021 investor letter hit your inboxes almost on the eve of the peak of this last bull market. It was tempting at the time to predict the turn of the market. But it had been tempting to do the same many times before, only to see it instead be the start of another bull market run. The question on our minds was rather: “should we ever try to predict the market?”. Our Popper-inspired answer was: “no”. Humans are simply too unpredictable for anyone to be able to make meaningful predictions about the future on broad topics such as market swings. One prediction we have learned to often be a safe bet, however, is that anything involving humans is likely to be volatile, but with a positive trajectory. As long as you can afford to wait. This is why Berkshire Hathaway has become one of the largest investment companies on the back of an insurance business rather than a fortune teller.

Sprints’ investment philosophy is based on the same premise: downside protection is an important ingredient in investing, even when focusing on high-growth companies. Our guiding document for new investments is our checklist, which is designed to catch weaknesses and risks in companies, rather than to predict the highest upside case.

Instead of spending our time predicting a weaker market we started to prepare for it. By the end of 2021, we created a ‘survivorship’ checklist inspired by Marathon Asset Management and Sequoia Capital’s retrospective analysis of characteristics of companies that had survived previous market crashes (included below). At the time we felt that our portfolio was well prepared for a potential market correction. However, few plans survive their first interaction with reality. A year into the downturn we have learned that the quality and speed of decision-making rank at least as high as any preparedness, or to paraphrase the legendary Prussian military strategist Carl von Clausewitz: “When things go against you it is better to act fast than to hesitate until the opportunity for good action is past”.

Companies, like Vinted, that immediately adjusted their cost base are now being able to go on the offensive. The ones that delayed their action are instead fighting a combination of shrinking financial flexibility and more discerning customers. This is the key reason why there are few new funding rounds being completed right now. The best companies are not raising and those that are could be referred to as “Groucho Marx companies”, in that investors refuse to join the cap tables of companies that want to have them as members.

Management’s attitude to the problem makes all the difference. In his essay “How Not To Die”, Paul Graham (founder of Y Combinator) explains that failed Y Combinator companies did not die from running out of money ‘mid-keystroke’ while they were busy closing deals or launching new features. Instead, “the underlying cause is usually that they’ve become demoralised”. In psychology, the core symptoms of demoralisation are loss of hope and meaning combined with pessimism or fatalism, in that one stops believing that any action today can lead to an expected improvement tomorrow. Demoralised managers are almost paralysed in front of hardship and spend their time finding excuses, scapegoats or creating wishful plans involving ‘the market’ saving them. Most companies only had to put up a sail to catch the wind of free money. Maybe long bull markets with an abundance of capital make people complacent. Or maybe it is part of human spirit to struggle to accept setbacks, change and fight back.

”Then the Lord said to Cain: Why are you angry? Why are you dejected? If you act rightly, you will be accepted; but if not, sin lies in wait at the door: its urge is for you, yet you can rule over it.”

Genesis 4:6-7 (New American Bible)

In the Bible, Abel brings his A-game to the pitch in the form of sacrificing the “fatty portion of the firstlings of his flock" Genesis 4:4 (New American Bible). God is delighted and accepts the offering.

His brother Cain, on the other hand, lacks the same customer focus and brings some random produce from his fields. God, knowing what good looks like from Abel’s sacrifice, is not impressed and rejects Cain’s offering.

But God is not the eternally judgemental customer that we contemporary snowflakes perhaps envision. He is a modern customer. He carefully fills out the customer review form at Cain’s checkout. If Cain had just cared to read it and act on it, he would have been able to win back God’s business. And humanity would have been saved from one of its most tragic stories. In his review God gave some simple pointers to managers experiencing hardship:

Despite receiving the world’s first management handbook, Cain cannot bring himself to improve. Instead, he turns all his focus on his more successful peer, Abel. Demoralised, filled with envy, self-deception and despair, he blames Abel for his failings and ends up killing him and losing both himself and his land in the process.

Similarly, the failing management teams that we come across are not failing because of lack of customer feedback, financial facts or management analysis. They often fail due to the spirit of Cain. Instead of being honest and transparent about the reasons behind both their own and the firm’s problems, they tend to blame external factors like the market, competitors and investors. With some high-level introspection, most managers would realise that simple measures such as continued customer focus and cost control would serve them better than other more convoluted alternatives.

In a recent episode of the excellent podcast “Founders”, the presenter - David Senra - concluded that frugality is likely one of the most common characteristics of successful founders. “If you could search every single episode of Founders the word frugal or frugality might be the most repeated phrase”, David Senra, episode 275.

For any student of successful businesses this is hardly news. The benefits of frugality are so obvious that it’s difficult to understand why not every business has this as its top priority. Additionally, the alternatives to getting your costs in order are not attractive:

Understanding this table does not require an MBA. However, we have found that highly educated people are the best at explaining, in very complicated ways, why one would not focus on cost efficiency and frugality despite overwhelming evidence that most great companies operate that way. Protecting corporate culture is a frequently used counterargument. Another argument is not wanting to rock the boat ahead of some wishful, low likelihood, external event they hope will happen to them. Most managers would never dream of running their household budget into massive debt because they do not dare tell their family there is no money, while hoping for a lottery win to bail them out. But for some reason things that are simple outside of work get very complicated inside an office.

In our experience, almost all great companies have had to go through several downturns and at least one near death experience. In hindsight, surviving them was necessary for their future greatness. Managers had the opportunity to streamline the company and surround themselves with people that worked well, even in bad times. And, perhaps most importantly, they had to focus on the things they were best at.

A useful showcase is how Amazon dealt with the dotcom crisis. To maintain trust with the markets and to prove the business model, Jeff Bezos decided to use the crisis to manage the business for profits for a year.

“After four years of single-minded focus on growth, and then just under two years spent almost exclusively on lowering costs, we reached a point where we could afford to balance growth and cost improvement…Focus on cost improvement makes it possible for us to afford to lower prices, which drives growth. Growth spreads fixed costs across more sales, reducing cost per unit, which makes possible more price reductions. Customers like this, and it’s good for shareholders. Please expect us to repeat this loop”

Jeff Bezos in the Amazon shareholder letter, 2001

.avif)

In the process he also helped define the business model of ‘scale economies shared’. In our portfolio, Vinted is an excellent example of this model. Despite already being one of the largest marketplaces in Europe – probably the largest one with integrated shipping – it uses its scale economies to continuously push down its shipping and payments costs while sharing those savings with its customers, widening the moat and making it harder for other marketplaces to compete. We expect other companies in our portfolio, such as Back Market, to be able to do this successfully over time.

“You’d rather chew off your arm…”

from the movie “Coyote Ugly”, 2000

Cain also serves as a good example for another human weakness. Not only did he lack customer focus, he was also vain and had a desire for power. Many managers confuse scale with size. Scale is most efficient when you are much bigger than your competition in your best discipline. Not when your volumes are scattered around many small markets or spread over several business units with low or no margins. Too often do companies fall in love with managing ‘global operations’, allowing them to colour vast areas on the global maps in their PowerPoint slides. It is an addictive behaviour. Once coloured, it’s difficult to retreat from a market regardless of whether it has enough scale and value. (The exclusion of the massive land mass of Russia since 2014 must have hurt many managerial egos). Examples of other vanity projects are to rapidly grow revenue by adding low gross margin products like re-selling hardware or going into e-commerce or consulting services. Once adjustments are made for all the extra overhead and other operational costs as well as the need to manage customer and supplier relationships, those projects are often loss-making. But getting rid of them will make your top line decline, which is a very painful experience for managers struck by size vanity. And for investors with a revenue multiple driven valuation methodology, any revenue, even if loss making, can create an illusion of value creation.

To be able to create an efficient high technology, high margin company, value destroying business units should be treated like dead branches that are cut off from a tree. Or, in times of distress, like animals that sacrifice limbs to save their lives. Companies should only focus on their best, most healthy and competitive businesses. Value destroying distractions in times of hardship are lethal.

A method often used by boards to create a sense of urgency in overfunded companies and to force more rapid change is to hide excess capital away in subtly described pockets such as ‘consolidation war chest’, or ‘rainy day fund’, just like you would hide alcohol from an alcoholic (more on that later). Another solution could be engagement. For example, looking at your internal efficiency in the context of ESG: why be wasteful with any resources? Don’t we owe it to ourselves and the world at large to treat everything we use as a unique scarce and depletable resource? Modern ESG warriors may find praise for inventing this as a novel approach to business. But a leader’s ability to drive resourcefulness has been a central feature of good management already since its very early days:

“We can see our forests vanishing, our water-powers going to waste, our soil being carried by floods into the sea; and the end of our coal and our iron is in sight. But our larger wastes of human effort, which go on every day through such of our acts as are blundering, ill-directed, or inefficient, and which Mr. Roosevelt refers to as a lack of “national efficiency,” are less visible, less tangible, and are but vaguely appreciated”

“The Principles of Scientific Management”

by Fred W. Taylor, 1911

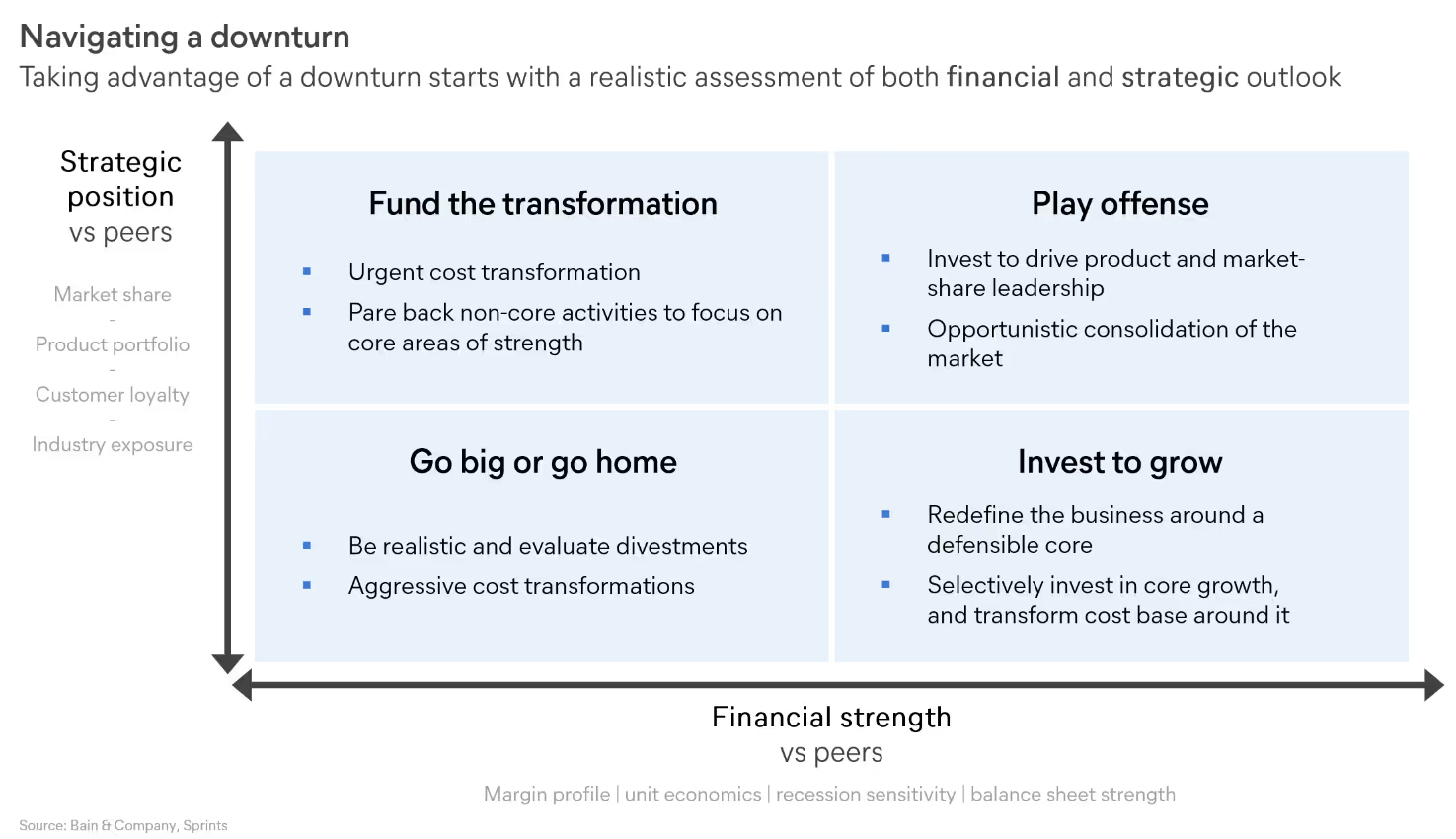

A do it yourself guide to navigating the downturn:

The Bain table above is a useful cheat sheet to navigate a downturn. It follows the simple principles discussed in this letter: i) quickly take down cost and make the organisation efficient, ii) sell, close or consolidate sub-scale or uncompetitive parts of the business, iii) use the freed-up resources to invest in your best assets as well as in future winners. Bain uses the metaphor of navigating a sharp curve on a racetrack. It is a hard test but the best place to gain an advantage: “The best drivers apply the brakes just ahead of the curve (they take out excess costs), turn hard toward the apex of the curve (identify the short list of projects that will form the next business model), and accelerate hard out of the curve (spend and hire before markets have rebounded)”. It may sound easy, but it is difficult and there are many demons to fight on the way.

“The helpful formula therefore is ‘spiritus contra spiritum”

Carl Jung in a letter to William G Wilson, co-founder of Anonymous Alcoholics

As most of us have likely experienced, changing a behaviour – even a bad one – is hard. The difficult part for a failing manager seems to be very similar to that of Cain or an addict: acknowledging that there is a problem, acknowledging that they are part of the problem and finding the right motivation to solve it. We have lived through many board meetings where there is one thing that we would like to hear more of: “My name is…, I am a founder/manager and I am a capital addict.”

It is not surprising, therefore, that it was students of Cain’s Old Testament parable that also came up with one of the most successful solutions to humanity’s self-destructive behaviour to date.

“We are all sinners and we all can change” was the “God to Cain” inspired mantra of the first version of Anonymous Alcoholics, an organisation with its roots in the Christian movement The Oxford Group. Its first set of “standards of morality” reads like any modern management or self-improvement literature of today: i) absolute honesty, ii) absolute purity, iii) absolute unselfishness, iv) absolute love. And anyone wanting to achieve successful change should pay attention to their principles: i) confidence, ii) confession, iii) conviction, iv) conversion, v) continuance.

The famous Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung was deeply involved in the first steps of creating Anonymous Alcoholics. Having failed with traditional psychology methods and reasoning, Jung concluded that the only way to make alcoholics change their destructive behaviour was to pursue a spiritual recognition and awakening.

“Ideas, emotions, and attitudes which were once the guiding forces of the lives of these men are suddenly cast to one side, and a completely new set of conceptions and motives begin to dominate them”

Carl Jung in describing the curing journey of a patient

Similarly, a founder that has spent too many years over-indexing on costs and fundraising while focusing on vanity metrics like revenue driven valuation, will need an awakening to change his modus operandi to frugality, consolidation and high returns on capital.

Jung cautioned that these experiences are “comparatively rare”. Changing beliefs is sometimes harder than changing management, which is why changing management is a well-established, often useful but equally often too long delayed management tool. As Warren Buffett also observed in the investment world:

“Our experience has been that the manager of an already high-cost operation frequently is uncommonly resourceful in finding new ways to add to overhead, while the manager of a tightly-run operation usually continues to find additional methods to curtail costs, even when his costs are already well below those of his competitors.” Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter, 1978.

Ultimately, the success of a company is the joint responsibility of shareholders, board and management. To be a positive force in improving the weaknesses that we have identified in our sector, we should start by strengthening and improving our own values and processes. What is better than starting with ‘capital’. As we have often stated, the greatness of capitalism has very little to do with capital. It is mainly about values and ideas. Capital itself is a cost or liability and raising capital from your investors should be compared to raising debt. The expectation is that it will be paid back with interest. The less capital you need to achieve your investment thesis, the better, which makes fundraises a strange thing to celebrate. In an effort to practice what we preach, we have dropped the word “Capital” from our name and we are now only “Sprints” and its online equivalent ‘www.sprints.com’.

Our aim with this battle cry for frugality, streamlined operations and capital efficiency is to try to reset some of the flaws we have seen in the technology industry over the last years. Firstly, managers should take back control and stop being dependent on investors whilst increasing dependency on their customers (and their efficiency in serving them) for their survival. Secondly, we owe it to ourselves, our companies, our employees and the world at large to use all resources as efficiently as we can. Frugality and customer focus does not destroy culture, it builds it. Employees of successful and resourceful companies have a much higher satisfaction and loyalty. And they have more fun:

“See business as a game, with a healthy sense of detachment. The way to keep the game challenging…is to never completely settle in but to always try to be better: not because it’s life and death, but because that’s what makes the game fun. Have fun at the game, and you’ll be better at it; get better at it, and you’ll more than double your profits. It works”, Bob Fifer, ‘Double Your Profits In 6 Months Or Less’, 1994. This is a book we wholeheartedly recommend for this Christmas. It is actually a much more fun read than the somewhat dry title gives away.

It is important to remember that not all costs are bad. As growth investors we thrive when investing in the right costs and on brave bets on the future. Without these, the world would soon be in a negative anorectic spiral. Just like Joseph Schumpeter described with his ‘creative destruction’, being resourceful and efficient frees up time and idle capacity for new innovations and growth. Or in the words of Paul Graham: “A culture of cheapness keeps companies young in something like the way exercise keeps people young.”

As we approach the holiday season after what feels like the end of a challenging year for many of us, we should remember that hope is a human obligation. Fighting the demoralised spirit of Cain and acting for a better future no matter how tough it seems is a critical feature in human story telling. In the Talmud it is described like this: “Imagine you are busy planting a tree, and someone rushes up to say that the Messiah has come and the end of the world is nigh. What do you do? - finish planting the tree before you greet the Messiah”. Islam has a similar story: “If the final hour comes upon you when you are planting a tree, finish planting it”.

As investors we love planting a tree when people think the end of the world is nigh. The last years have included dramatic shifts and managerial challenges. But we think we have laid the ground for many good years to come. The Sprints team looks forward to the next years of forest management, branch cutting and…not least…tree planting.

Sincerely yours,

Henrik and the Sprints team

London, 20th December 2022