Before discussing the recent events in the markets, we will start by discussing our portfolio valuations - one of the few stable developments recently. Having brought these down sharply last year, we remain comfortable with their levels, which are primarily driven by public market comparables. The underlying fundamentals of our companies are healthy and we are seeing development and strengthening throughout our portfolio, largely as a result of the intensive value-add work we have been undertaking.

We are equally active in scouting new investments. Like our portfolio companies, most late-stage businesses are focused on optimising their operations for the new environment, and those that need to raise capital are often in such a state that we would rather pass on them than take on their problems.

There are signs of improvement. Valuations of listed tech companies have recovered ground in 2023, while valuations in the private markets remain at ~50% discount on the last round. This has increased investors’ conviction in their own portfolios and the share of secondary transactions that are being pre-empted by existing investors has increased from 6% in 2022 to 11% so far in 2023 (compared to 10% in 2021 and 18% in 2020). To that point, increasing our ownership stake in our existing portfolio companies has been our primary area of investment activity in the last year (through Vinted, Booksy and one smaller investment, yet to be announced).

“If the universe wasn’t huge and empty and violent with exploding stars and so forth, we couldn’t be here at all. So it couldn’t have been otherwise if we are to live. One requires as a human being to face up to the overall problem of being alive”

Anthony Hewish

Radio astronomer and Nobel laureate in Physics in 1974

As mentioned at the outset of this letter, the valuation of our portfolio was a rare constant in the last quarters. In March, First Republic Bank lost $100 billion in deposits and became the second largest bank ever to collapse in the US. This followed the collapse of the most dominant bank in the tech sector, Silicon Valley Bank. Our exposure was minimal, affecting only a few of our companies. Regardless, having a single banking relationship has now been added to our investment checklist a.k.a. our internal book of misery, where it sits together with other low probability, high-cost events such as poor cyber security protection and contractual myopia.

Bank runs are the latest twist in what is turning out to be an eventful period. We have experienced multiple Covid outbreaks, political turmoil around the world, a war on European soil, a protracted energy crisis and the return of high inflation. To name but a few. Turbulence is how we roll, and both newspapers and financial markets are constantly over-enthused with doomsday drama.

Biologists would be a little less worked up about it. To them, this turbulence fits well into what they would call “life”. Life in the biological definition is not for the faint hearted. The ability to evolve, grow and develop, adapt to change, reproduce and eventually die are all characteristics that a biologist wants to see to rubber stamp anything as living.

Economists have often had a complicated relationship with the exuberant life in the markets they study. Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter coined the term “creative destruction” to describe these phenomena in the economy and thought of depressions as a “good cold shower” for capitalism. Harry Markowitz, the first modern finance economist, defined the changes as variance and volatility and started a long tradition of wanting to curb, manage and ultimately avoid these perceived investment risks. Meanwhile, many macro economists have been concerned with how to save existing economic life from the cycles of destruction by providing life support.

To be fair to economists, life and living are puzzling to most people and sciences. In the 1960s mathematician and meteorologist Edward Lorenz pioneered Chaos Theory to try to explain how interconnected yet highly unpredictable systems work. The butterfly effect, where a butterfly flapping its wings in one part of the world can cause a tornado in another part is a popular simplification of this theory. And despite humanity being born out of living chaos, our minds are not designed to appreciate its beauty. Chaos Theory stands at a degree of difficulty that is too high for most of us to understand and we struggle to appreciate its benefits. Complaining about the weather is a strong contender to complaining about the economy and the stock market. Prior to the publication of popular versions of recent research, various religious systems have had to carry most of the explanatory burden of where we came from and why we are here.

We have started most of our recent letters by complaining about the high volatility in our markets. Our intention was to start this letter in a similar fashion. But instead, it got us thinking - complaining about something that is a constant feature of the economy, our markets as well as life in general is pointless (and repetitive). Plus, hearing a growth investor complain about change is counterintuitive. Instead, this update will embrace the tough love of life and its turbulence. Not all change is good. But cycles of change, disruption and volatility are what moves us forward. And without them we know what the biologist would call us – dead.

“It is better to live outside the Garden with her (Eve) than inside it without her”

Mark Twain

Diaries of Adam & Eve

The conflict between our longing for still perfection and the volatility of life began already when Adam and Eve made their entrance into the world. It did not take long for them to wreck the perfection of Eden and be relegated. This disappointing performance continued with the next generation. Case in point, in our last letter we left Cain as he was exiled to dwell in the land of Nod, east of Eden, having failed to please God and killing his brother in a jealous rage. In modern venture lingo, our ancestors’ rapid fall through the league system indicates a lack of product-market fit between the lively imperfection of humans and the idealised perfection of Eden.

It is easy to fall into the trap of criticising our ancestors in the same way as we complain about the changes in the world around us. However, as their descendants, their failings are ours. And the current swings in the markets are caused by all of us. Ludwig von Mises, a predecessor to Joseph Schumpeter among the Austrian economists, didn’t see our shortcomings as something negative. Instead, he thought of human imperfection as a necessity for progress.

“It is vain to refer to the imperfections and weaknesses of human life if one aims at depicting something absolutely perfect. The very idea of absolute perfection is in every way self-contradictory… the absence of change—i.e., perfect immutability, rigidity and immobility—is tantamount to the absence of life. Life and perfection are incompatible”

Ludwig von Mises

Human Action

The annual World Happiness Report provides some anecdotal evidence to his argument. Societies that are less lecturing about human imperfection seem both happier and wealthier. The report ranks intuitive happiness indicators like GDP per capita, life expectancy and individual freedom. One thing it does not measure, but which has a surprisingly high correlation with happiness, is “lack of religiosity”. The correlation between lack of religiosity and happiness is, for example in line with GDP/capita (a proxy for wealth) and higher than Government expenditure/GDP (a proxy for safety net). Most countries in the top of the happiness index are in the bottom of the religiosity index and vice-versa.

.avif)

The ranking also illustrates the difference between a modern and a more traditional society. Aiming to live a still and perfect life on Earth to qualify for a great life in heaven was the modus operandi in the world for most of the last millennia. The French mathematician Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) even pioneered decision theory and probability thinking with the famous Pascal’s wager. In this, he argues that every rational person should live as if God exists and seek to follow all religious rules and traditions during his time on Earth. The downside, he argued, is only finite loss of vain things such as consumption and pleasures. If God exists, a perfect life on Earth will be rewarded with infinite gains in the afterlife (as well as not having to endure infinite loss in hell). To lure modern humans into this deal we would expect that he would have to produce numerous online reviews and customer surveys of this heavenly second order experience before anyone would volunteer.

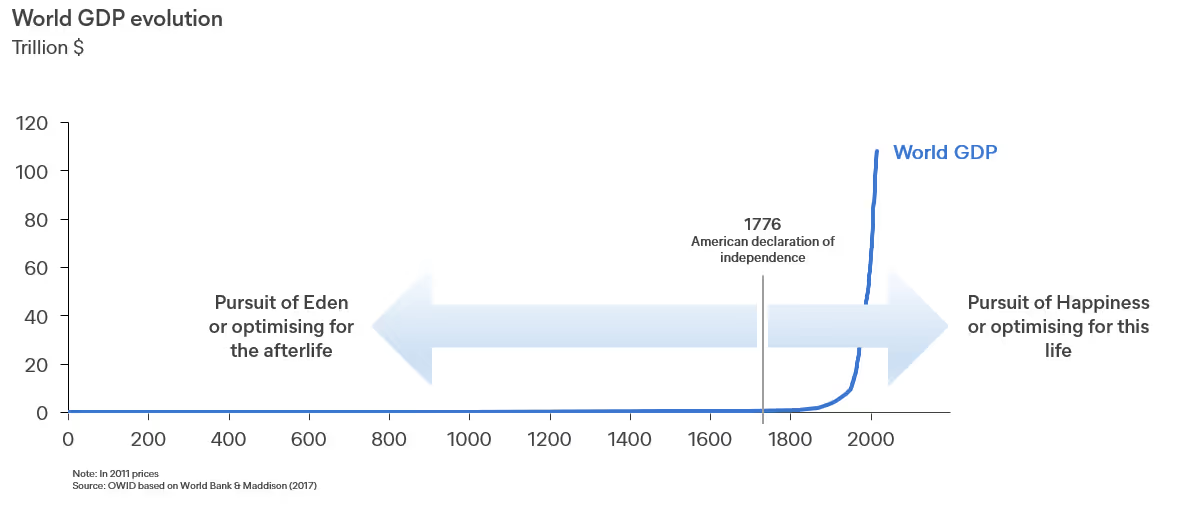

It can be argued that the world formally changed from Pascal’s wager of “life, no liberty and a pursuit of Eden-like perfection” to a modus operandi of “life, liberty and a pursuit of happiness on Earth” with the American Declaration of Independence in 1776. In hindsight, we can see that this massive shift in life ideal, and the subsequent unleashing of human spirits, coincided with a remarkable acceleration of economic growth in the countries choosing this path, as seen in the graph overleaf. Unfortunately, we lack any similar data on the level of success people have experienced in their afterlife, explaining why Pascal’s wager is still unsolved.

“I no longer trust novels which fully satisfy my passion to understand”

Susan Sontag,

American philosopher

Despite this recent unleashing of our growth spirits, our longing for inertia is still strong. In their Nobel-winning paper “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk” Daniel Kahneman and Adam Tversky identified a number of interesting human behaviours. One was the Certainty Effect, which describes how people prefer guaranteed outcomes and discount probable ones, even if the latter statistically produce better results. For example, most would choose a certain profit of 50 rather than a 75% probability of making 100.

Humanity’s preference for certainty and risk aversion ahead of higher but only probable outcomes often plays an important part in financial scandals. Enron’s fraudulent accounts aimed to describe the company as controlled and stable despite its wildly leveraged and volatile underlying operations. Long Term Capital Management’s investment thesis focused on risk-free returns using smart derivative strategies and allowed it to raise billions while sleepwalking into one of the biggest Black Swan events in financial history. More recently, both Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank built their large and growing books on the assumption that the low volatility and low interest rate environment would remain unchanged, despite humanity’s low ability for controlled behaviour. In his latest shareholder letter, Jamie Dimon, the Chairman and CEO of J.P. Morgan, pointed out that the failure to prepare for volatility was not just a bank management problem. The Federal Reserve’s stress tests of banks never incorporated the scenario of higher interest rates. Meanwhile, the regulator also incentivised banks to hold government securities by demanding very low capital requirements in exchange. The increasing volatility in those, perceived safe, securities was what later got the banks into trouble. Regulating or running a bank on the assumption of a never ending stable financial environment is as risk-free as driving a car at the speed limit without watching the road or the traffic around you (come to think of it, the traffic is another chaotic system humans regularly complain about).

The Madoff Investment Securities fraud is perhaps the most interesting illustration of our dangerous fascination for static perfection. His performance was entirely made up and had no connection to any actual investment activity. Given his success in attracting capital, one could assume that Madoff created the most beautiful financial love poem ever to lure his investors. So, what did he come up with? High returns? No, Madoff’s made-up returns were typically no better than those produced by the S&P Index. Instead, the holy grail of finance that Madoff made up to attract investors to his Ponzi scheme was…low volatility. With negative 0.55% being his weakest month on record and never having losses for two consecutive months, Madoff spoke to our industry’s longing for perfectly calm markets and investing strategies. The same pundits that never hesitate to call the volatile behaviour in our growth markets “irrational” seem to think that it is perfectly rational that life’s benefits of growth and high returns can co-exist with a flat ECG curve. Sadly, there is a price to pay for that illusion: namely, lots of volatility and no returns.

This fascination for unrealistic expectations of life is not isolated to finance professionals. On a side note, recent research suggests that the rapidly deteriorating mental health among teenagers can be traced back to a similar longing for unrealistic perfection. When scrolling through posts of people’s seemingly “perfect” lives on social media they, like their older relatives lured in by Madoff, start to believe that life can exist in absence of any of the characteristics of life, such as volatility in investing, rain, wardrobe misfits, random arguments, messy houses and junk food in real life. To add insult to injury, young people routinely engage in “harsh self-punishment” to try to live up to the unrealistic expectations of how they should look and what they should own.

“Young people are seemingly internalizing a pre-eminent contemporary myth that things, including themselves, should be perfect”

Perfectionism Is Increasing, and That’s Not Good News,

Harvard Business Review.

As general advice to any parents and teenagers reading this: if you see something that is missing all the characteristics of life, it most likely does not exist. At least not IRL…

“Come to think of it, there is no safe level of living, but nobody would recommend abstention”

Dr David Spiegelhalter

Winton Professor for the Public Understanding of Risk at Cambridge University

Our risk averse attitude does not only overweight certainty in our decisions. It also increases our appetite for negative forecasting. If pet dog owners were to google why their dogs are constantly barking, they would quickly find the academic term for it - Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD). Their neighbours do not need Google to find the name for it. As we have discussed in previous letters, investors know this as a never-ending flow of bubble alerts from famous economists and other pundits. Given its frequent appearance in all walks of life, hyperactive risk detection was probably a successful strategy when nature was a more dangerous place to live in than today. However, when most of our immediate risks have been mitigated, this detection system has more flaws than benefits as it constantly short circuits long-term thinking and investing. We should balance our short-term risk detecting brains with longer-term risk exposure and management of that exposure. Maybe the “irrational exuberance” in our markets is not occasional high valuations. But rather the expectation of low or no volatility in human economic life and the constant “barking” about it. We should train the next generation of watchdogs to bark when things seem too still and quiet to be real.

A century after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Darwin published his book ”The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex”. One of the carrying theses in the book was that embracing life and taking risks to reproduce faster was a more successful survival strategy for many species than playing it safe and mating slower. One of the carrying pieces of evidence was the colourful feathers of peacock tails, which had always puzzled Darwin. Why had natural selection produced something that visible and intricated in male peacocks? Darwin’s conclusion was that the only evolutionary sense this made for males was to win the interest of females. The higher the risk and the energy invested into doing so was compensated by higher reproduction rates and growth. Recent research has suggested that the higher this investment is, the higher the chance of success, as the investment is seen as genuine and honest by the receiver. Many will recognise the same logic in engagements, where the size of the rock is hoped to have a similar correlation with success.

Successful entrepreneurs often fit this “peacock-model”. The greatest founders we know all participate in important customer pitches and customer relationship calls. For a young company there is nothing more precious than its founder’s time, and spending it on key customers will be perceived as the ultimate commitment by the receiver. Similarly, according to a study by the German Institute for Economic Research and the University of Münster, self-made millionaires are more open and extroverted than the general population and, unsurprisingly, more risk tolerant.

The same risk-taking strategy also seems to hold true for early-stage VC funds. The highest returning funds follow the Babe Ruth mantra of “I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big” and typically have a counter-intuitive high share of write-offs. The higher investment risk needed to find ground-breaking companies seems to be warranted (we would expect Harry Markowitz to caution here that anyone needing to live off their investment income should favour a diversified portfolio rather than put all their eggs in a single Babe Ruth inspired VC fund. But, for the overall economy, the existence of many such funds is likely a good thing).

“He who sees the past as surprise-free is bound to have a future full of surprises”

Amos Tversky

Israeli psychologist

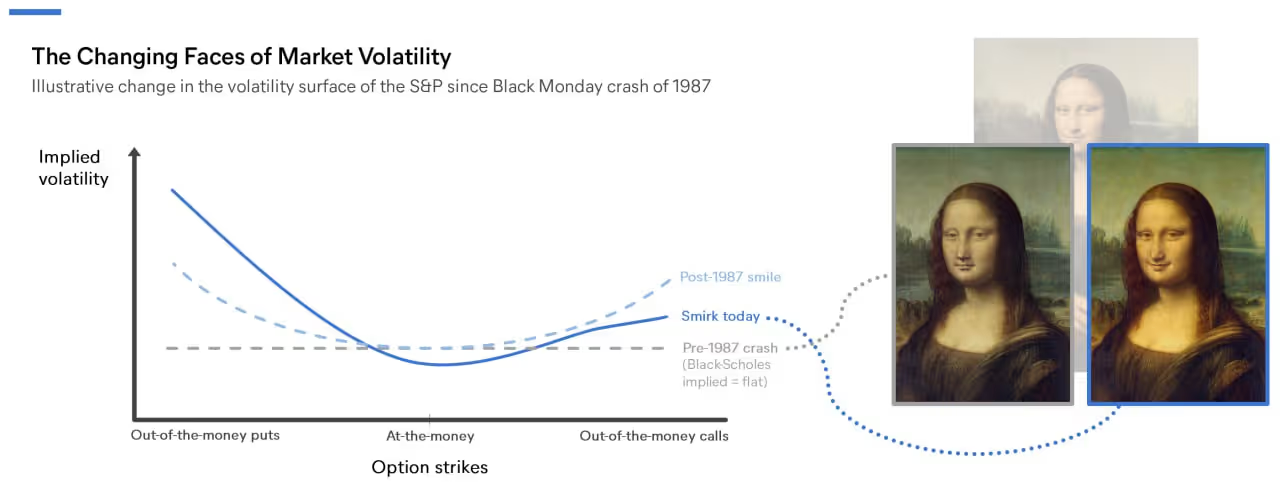

The few people that embrace peacock-like risk and volatility (other than tech investors) are modern derivative traders. The invention of the Black-Scholes model in the 70s started a rapid boom in the derivatives market. The first generation of traders grew up with a model based on the assumption that the volatility for an option with the same duration is the same across all strike prices. This held true up to the stock market crash of 1987 when traders realised that unpredictability, fat tails and volatility played a bigger part in life than the academic models had assumed. Practically this meant that the chance/risk of far out of the money options getting in the money was higher than previously expected. This realisation led to an increase in price (and thus implied volatility) for out of the money options, creating a chart that looked like a smile when you plot it on a graph. This was the birth of the volatility smile, the most beautiful celebration of volatility – or life, if you may – that normally risk-averse investors have ever produced. However, nothing lasts long in the lively financial markets. After the financial crisis of 2008, the market started to treat upside and downside risks differently, resulting in a smirky smile.

So, life is volatile and risky. And in the “smiling” derivative markets this is increasingly getting its deserved attention. Should other investors worry about it? Experienced investors like Howard Marks and Warren Buffett always argue that long-term investors have less to fear from short-term swings in the market. Similarly, in his 1952 Nobel prize winning paper “Portfolio Selection”, Harry Markowitz came to a similar conclusion. Investors should not try to avoid risk or volatility, but rather try to combine many different types of risks. A portfolio of uncorrelated assets – each of them with potentially high risk – can be almost risk free, as the development of the different assets even each other out. This probably also applies to a large and diversified economy. Despite all the big, negative events mentioned in the beginning of this letter, the world economy seems surprisingly fine. For every negative front page describing a single large negative event, there are likely a million uncorrelated and less newsworthy positive things happening. The best way to build resilience in an economy is to promote diversification and competition rather than trying to manage risk by regulation, concentration or keeping uncompetitive companies alive. Or to quote Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book Antifragile: “The more variability you observe in a system, the less Black Swan prone it is”.

“Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome”

Charlie Munger

The headline of the SVB collapse was duration mismatch of assets and liabilities. The collapse also highlighted another duration problem in our markets. The one between short-term and long-term investors and their remuneration structures. The growth in tech investing in recent years has, in large parts, been driven by non-traditional VC investors such as investment banks, hedge funds, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and corporates chasing outlier returns away from the zero-interest environment. Employees in these firms are often remunerated with annual cash bonuses based on book values and on internal rates of return rather than on distributed cash returns and money multiples. These adverse remuneration structures become particularly problematic in a downturn when what looked like a smart short-term yield enhancement trade, turns into a decade long turnaround and company building project.

The problem arises when the interests of these new venture investors collide with the interests of their portfolio companies. The latter are best off by shrinking to focus on their core products and markets, reaching profitability and if needed raising new capital from the best investors they can find, at market prices. In contrast, their short-sighted investors resist negative first order consequences. Instead, they try to freeze the world in 2021 by funding inefficient operations with debt-like instruments that do not impact the size of the company or the last round valuation. A founder should always select investors that are aligned with the long-term success of the company.

This weak fit between short-term remuneration structures to solve long-term problems reminds us of the half serious example of military remuneration structures in the classic paper on remuneration by John Kerr of Ohio University “On The Folly Of Rewarding A, While Hoping for B”:

“Let it be assumed that the primary goal of the organization (Pentagon, Luftwaffe, or whatever) is to win (the war). Let it be assumed further that the primary goal of most individuals on the front lines is to get home alive. Then there appears to be an important conflict in goals.”

Most traditional venture and private equity funds are set up to be able to deal with long wars of attrition by raising ten-year capital and only pay out any eventual profit sharing based on distributed cash to its investors. At Sprints we also use European waterfalls and long vesting periods to maximise our alignment with both the value creation of the company and the value distributed to our investors.

With a relatively high company and industry concentration, Sprints’ portfolio is not designed in the spirit of Markowitz’s portfolio selection. Instead, we aim to mitigate our concentration risk by operating within our domain expertise, carefully selecting the best companies to invest in while working closely with them during our time as investors. We constantly work to improve our checklist and our due diligence process and we aim to be at the top of our industry in terms of companies analysed per investment completed and number of active partners per portfolio company. Last but not least, we have time. We have found that among the best ways to manage volatility is not to avoid it but to combine quality assets that get better over time… with time. The same quality and long- term focus also allows us to take advantage of a weaker market rather than being its victim.

“I can’t believe in a heaven which is just passive bliss. If there is such a thing as a heaven it will contain movement and change”,

Graham Greene

English catholic author and journalist

To finish off where we started, humanity will be better off if we accept and embrace life with all its imperfections and constant changes, instead of idealising static unattainable perfection. That acceptance will also make us more focused on quality and growth. The best long-term strategy for our society is likely a high level of experimentation and risk taking over the long term. Especially for our younger generations. As discussed, humans are wired to choose unambitious and certain outcomes. As a one-off trade it would not matter much. But if you are young and you make the same suboptimal safety bet ahead of a bigger probable opportunity not only one time, but hundreds or perhaps even thousands of times during your life, the compounding effect is life changing. It is the difference between being an employed burger flipper or a highly educated executive or an entrepreneur. Nature’s irony is often to deny us of what we want the most. Someone choosing to live by making safe sub-optimal choices may realise that the safety they believed in was an illusion. Safety and certainty are not part of the biological definition of life.

In “The Descent of Man”, Darwin offered a similar tough love deal to his readers. He rightly expected that the fact that we are not created to godlike perfection but rather “descended from some lowly organised form” to be “highly distasteful to many”. But the silver lining from that realisation was that humanity had the potential “for a still higher destiny”. Maybe it was a sign of hope that we can appreciate the realities of life (or maybe it was just a sign of England being the land of eccentric horticulturists). But Darwin’s last book “The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms” was the bestselling book during his lifetime, with thousands of copies sold within weeks of publication.

In describing the root cause of our origin, behaviour and preferences, Darwin’s indirect influence on economics cannot be underestimated. Both Markowitz and Schumpeter ranked his “The Origin of Species” as the greatest scientific book of all times. Of the two, Schumpeter most actively brought Darwin’s logic to the economic sciences.

“Industrial mutation—if I may use that biological term—that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in”, Economic Cycles by Josef Schumpeter.

Sprints is living, with our volatility smile on…:-S. Investing in great growth companies with a ten-year horizon is an exciting privilege. However, every decade will likely include periods of weak markets and costly mistakes. Creating a firm that can tackle these and hopefully also improve and evolve over time is one of the competitive edges that we can thrive on.

Sincerely yours,

Henrik and the Sprints team

London, 18th May 2023